Quick Guide to Mallard Ducks

You've seen them a thousand times. On the pond at the park, in a nature documentary, maybe even on your dinner plate. The mallard is that duck everyone thinks they know. But here's the thing – most of us only scratch the surface. We see the green head on the male and think, "Yep, that's a mallard." End of story. But what about the mottled brown female? What about where they go in winter, or the weird sounds they make, or why they're so successful almost everywhere? That's where it gets interesting.

I remember spending hours as a kid trying to spot the iconic green head at a local wetland, completely ignoring all the brown ducks, thinking they were some "other" kind. I was wrong, of course. That's a common mistake. This guide is here to move past just the pretty picture and dig into what makes Anas platyrhynchos – the mallard – tick. We'll talk identification (for real, including the tricky ones), behavior that might surprise you, and even touch on what it's like to have them around more permanently. No fluff, just the stuff that actually matters if you're curious, a birder, or just someone who likes to know more about the wildlife in their backyard.

Spotting a Mallard: It's Not *Just* the Green Head

Let's get the basics down first. If you only learn one thing, let it be how to tell a mallard apart from its look-alikes. It's more than just a color check.

The Classic Drake (Male)

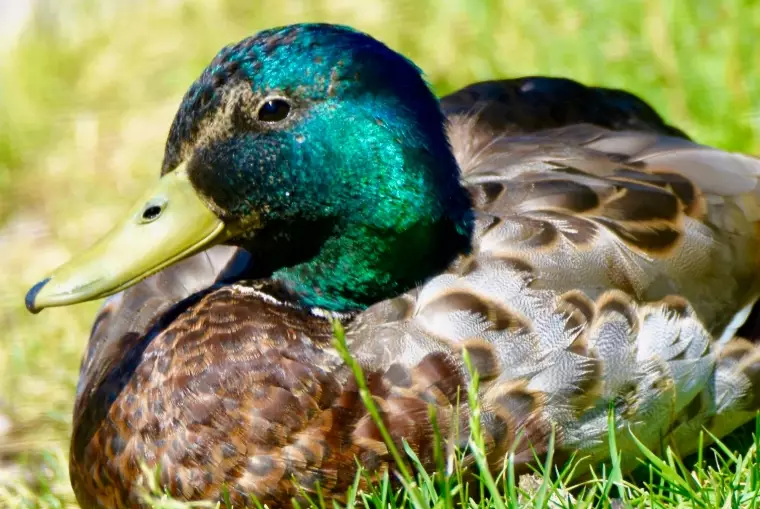

The breeding male mallard is the poster child. That iridescent green head is stunning in direct sunlight, shifting to almost blue or purple depending on the angle. It's set off by a thin white collar. His chest is a rich, chestnut brown, and his back and sides are a pale gray. Then you have the black rear end (the "rump" and curled central tail feathers, called drake feathers) and the bright orange legs and feet. The bill is a solid, yellowish-green.

Honestly, the first time you see one up close, that green can look almost too bright, a bit plastic even. It's a real standout.

The Often-Overlooked Hen (Female)

This is where many casual observers get tripped up. The female mallard is all about camouflage. She's mottled brown overall, perfect for blending into reeds and grasses while on the nest. The key marks to look for are her orange-and-black bill (orange on the sides, black on the top and tip) and the distinct, dark smudge through her eye (the "eye-line"). Her tail is also pale, almost white, which you often see when she's swimming. She lacks the drake's curly tail feathers.

I can't stress this enough: if you see a brown duck with an orange-and-black bill at your local pond, it's most likely a female mallard. Don't overcomplicate it.

Eclipse Plumage and Juveniles: The Confusing Phase

Here's a curveball. After breeding season, the dazzling male mallard molts into a drabber set of feathers. This is called "eclipse" plumage. For a few months in late summer, he looks remarkably like the female – brown and mottled. But he usually retains a few giveaways: his bill stays that dull yellowish-green (not orange-and-black), his chest might be a bit reddish, and his overall color can be warmer brown than the female's. It's a tricky ID, and even experienced birders sometimes pause.

Juveniles look like a slightly messier version of the female until they mature.

Mallard vs. The Look-Alikes: A Quick Comparison Table

This is where a table really helps. You see a duck that's sort of mallard-like, but something's off. Check this.

| Duck Species | Male Key Differences from Mallard Drake | Female Key Differences from Mallard Hen | Common Confusion Point |

|---|---|---|---|

| American Black Duck | Entirely dark brown body, no gray sides. Greenish-yellow bill. | Very similar to female mallard! Darker body, no distinct eye-line. Bill is greenish-yellow, not orange/black. | Female/ eclipse males are super close. Bill color and overall darkness are the best clues. |

| Mottled Duck | Similar to female mallard but with a clear yellow/green bill, no eye-line. | Almost identical to the male. Lacks the mallard hen's orange/black bill and strong eye-line. | Range is key (Gulf Coast, Florida). The uniform bill color is the dead giveaway. |

| Northern Pintail | Elegant, long neck and tail. White breast with a brown head. | Sharper, more patterned brown feathers than mallard hen. Gray bill. | The silhouette is totally different—much more streamlined. |

| Gadwall | Subdued gray-brown with a black rear. Complex gray patterning. | Sharper facial pattern than mallard hen, often with a white speculum (wing patch) in flight. | Males lack any bright colors. They're the "business casual" version of a duck. |

See? The black duck is the real troublemaker for identification. If you're in the eastern US and see a very dark, mallard-shaped duck, check that bill.

Beyond the Looks: How Mallards Actually Live

Knowing what they look like is half the battle. The other half is understanding what they're doing. Their behavior explains why they're everywhere.

Habitat: They're Not Picky

This is the secret to the mallard's success. They are habitat generalists. While they love shallow wetlands, marshes, and ponds (their natural homes), they have absolutely capitalized on human changes to the landscape. Think:

- Urban and suburban parks with ponds

- Farm ponds and flooded agricultural fields

- Slow-moving rivers and creeks

- Even retention ponds in shopping centers

If there's water, some vegetation, and a bit of food, a mallard will probably give it a try. This adaptability is unmatched by many more specialized ducks.

The Diet of an Opportunist

Mallards are dabbling ducks. You'll see them tip-up, tails in the air, to reach aquatic plants, seeds, and invertebrates in the shallows. But their menu is huge. It includes:

- Seeds and grains (they love farm fields after harvest)

- Aquatic plants and their roots

- Insects, worms, small crustaceans

- And yes, in urban settings, they'll gladly take handouts like bread or birdseed (though feeding them bread is a terrible idea—it's like junk food and pollutes the water).

This flexible diet means they can find a meal in almost any season and location.

Sounds and Social Life

The female mallard has the classic, loud "QUACK" that everyone associates with ducks. It's often a series of quacks, sometimes accelerating when she's excited or alarmed. The male's voice is quite different – a softer, reedy "kwek" or a low whistle. You can hear a library of their calls on the Cornell Lab of Ornithology's Mallard sound page, which is an fantastic resource for comparing.

They're social outside of breeding season, often forming large flocks. But they can also be quite territorial during spring.

The Annual Cycle: From Courtship to Migration

Their year has a rhythm, and it's worth knowing if you want to predict their behavior.

Winter: This is flock time. You'll see large groups on any open water that isn't frozen. They're focused on conserving energy and finding food.

Spring: Pairs form or re-establish. The famous "head-pumping" and whistling displays of the males are common. They start looking for nesting sites. Not all mallards migrate huge distances; many in temperate areas are year-round residents if food and open water persist.

Summer: The female is on the nest, hidden away. The male often leaves once incubation is well underway (the so-called "drake molt migration" to safer areas) to go into his eclipse plumage. Ducklings are everywhere by early summer – a line of fuzzy yellow and brown chicks following mom. This is a vulnerable time; predators like foxes, raccoons, and large fish take many.

Fall: Families regroup, birds that migrated north return south, and flocks build again. The males return to their bright plumage.

Mallards in Your World: From Birding to Backyard Ponds

Birding and Photography Tips

Because they're so common, mallards are great practice subjects. For photography, early morning or late afternoon light makes that green head glow. Get low to the water's eye level for more engaging shots. Watch for interesting behaviors – the dabbling, the interactions, the preening. Don't just shoot the static portrait.

For listing purposes, pay attention to those tricky females and eclipse males. Confirming an ID based on bill color and speculum (the bright blue wing patch bordered in white, seen in flight) is good practice.

Considering Mallards for a Pond or Homestead?

This is a big topic. Mallards are often people's first thought for a backyard duck. They are hardy, generally calm, and can be beautiful. But there are real considerations.

If it's legal and you're committed, here's a quick list of what mallards need that chickens don't:

- Water to submerge their heads: They need to clean their eyes and nostrils daily. A deep tub or small pond is essential, not just a drinking cup.

- Messier housing: Ducks are famously wet and messy. Their bedding (straw or pine shavings) gets damp quickly and needs frequent changing.

- Different diet: While they'll eat chicken feed in a pinch, they need a waterfowl or waterfowl-formulated feed for proper nutrition, especially during breeding. Niacin is a critical component.

- Protection: They are very vulnerable to predators at night. A secure, locked coop is non-negotiable.

They can be delightful—more interactive than chickens in some ways, with their constant soft chattering. But they are not low-maintenance pets. The pond will get mucky, and you will be cleaning a lot.

Mallard Questions You Were Too Embarrassed to Ask

The Bigger Picture: Conservation and Our Role

The mallard is not endangered. Far from it. Its population is managed as a game species, and wetland conservation efforts (like those by Ducks Unlimited) that benefit mallards also benefit countless other species that need those habitats. So in a way, the mallard's popularity helps fund broader conservation.

But our direct interactions matter. Feeding them bread leads to malnutrition, water pollution, and disease (like "angel wing," a deformity). It also causes overpopulation at artificial sites. Enjoy them from a distance. If you must feed, offer something appropriate like cracked corn, duck pellets, or frozen peas—sparingly.

Providing natural habitat is the best thing. If you have space, a pond with native plants at the edges will attract them naturally and give them proper food. They'll come and go as they please, which is how it should be.

Look, the mallard is a survivor, a generalist that has ridden the wave of human landscape change. That's why it's everywhere. But "common" doesn't mean simple. From the intricacies of its molt to its role in ecosystems and even its complicated relationship with us, there's always more to learn. Next time you see one, take a second look. Check the bill. Watch what it's eating. Listen to its call. You're looking at one of the most successful, adaptable, and fascinating birds on the planet.

And maybe, just maybe, skip the bread.

Reader Comments