Quick Navigation

- Why the Green Head is a Male Mallard's Signature

- The Exceptions: When You Might See a "Female" Mallard with Green

- Mallard Look-Alikes: The Hybrid Factor

- How to Actually Tell Male and Female Mallards Apart (It's Not Just the Head)

- Common Questions Birders Ask (The FAQ We All Need)

- Final Thoughts: Embracing the Uncertainty

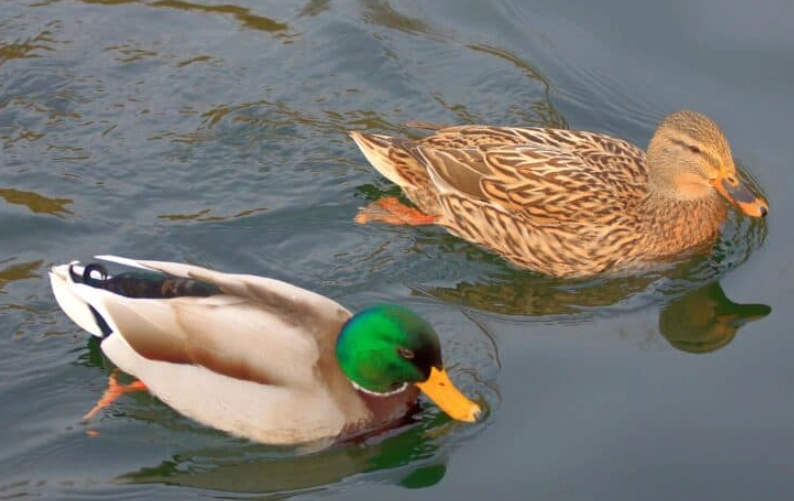

So you're out by the pond, binoculars in hand, and you spot a duck with a glossy green head. Easy, right? That's a male Mallard. Everyone knows that. The males are the show-offs with the emerald-green noggins, the chestnut chests, and the classic curled tail feathers. The females? They're the masters of camouflage – all mottled browns and tans, perfect for hiding in the reeds while nesting.

But then... you look closer. Something's off. The body shape seems a bit fuller, the behavior a bit less flashy. And a nagging question pops into your head: Can female Mallards have green heads? It sounds like a trick question, like asking if tigers can have stripes. But the world of birds, especially ducks, is full of surprises that don't fit the neat pictures in our field guides.

I remember one chilly morning at a local wetland, convinced I'd found a weird hybrid. The duck had a subdued, patchy green sheen on its head but the overall posture of a female. I spent ages flipping through my guidebook, frustrated. It turns out, the answer isn't a simple yes or no. It's a fascinating dive into hormones, genetics, age, and the sheer unpredictability of nature. Let's unpack this puzzle together, without the textbook jargon.

Why the Green Head is a Male Mallard's Signature

First, we need to understand why the green head is such a big deal. In the duck world, looks are serious business. That brilliant green isn't a pigment like the brown in the feathers. It's structural color. It's all about physics – microscopic structures in the feather barbules reflect light in a way that creates that shimmering emerald and blue effect. You see it in hummingbirds, peacocks, and our male Mallards.

The development of this glamorous plumage is driven by sex hormones, primarily testosterone. When a male duck matures, testosterone triggers the growth of these specially structured "eclipse" and then "nuptial" plumage that includes the green head. It's an advertisement. It screams "I'm healthy, strong, and good mate material" to the females and "back off" to rival males. The female's muted palette, on the other hand, is for survival. Being invisible on a nest is a far more valuable trait than being flashy.

So, under normal, healthy conditions, a female Mallard's hormonal recipe doesn't include the ingredients to cook up a green head. Her body simply isn't geared for it. That's why the standard field guide image is so reliable 99% of the time.

The Exceptions: When You Might See a "Female" Mallard with Green

This is where it gets interesting. Nature loves breaking its own rules. If you're staring at a duck that has female-like traits but a green-tinged head, you're probably looking at one of these characters:

The Confusing Young Male

This is the most common reason for confusion. Male Mallards don't hatch looking like their dads. They go through a lengthy adolescence. For much of their first year, juvenile males closely resemble females. They're the same mottled brown.

As they approach their first breeding season (usually in late fall or winter of their first year), they start molting into their adult finery. This molt isn't instantaneous. It's patchy. You'll get a young drake with a mostly female-style brown body but with splotches of green starting to appear on the head and neck, maybe a few chestnut feathers popping through on the chest. It looks messy and confusing. Is it a female Mallard developing a green head? No, it's literally a teenage boy, halfway through his awkward glow-up.

I find these transitional birds the hardest to ID. They have the body of a hen but the face of a future drake.

The Hormonal Oddity (Intersex or Hormone-Imbalanced Birds)

Now, this is the rarest and most scientifically intriguing scenario that directly addresses the core question: Can female Mallards have green heads? In extremely rare cases, yes, due to hormonal abnormalities.

Birds can experience intersex conditions or develop ovarian tumors that secrete male hormones (androgens). If a genetic female (with ovaries) produces enough testosterone, her body can be tricked into developing male plumage characteristics. This could result in a mostly female-shaped duck with a partially or fully green head, or other male features like a curled tail feather.

It's important to note this is not a choice or a phase; it's a biological anomaly. These ducks are true genetic females experiencing a hormonal disruption. You can read about the complexity of avian sex determination and hormonal influence on the Cornell Lab of Ornithology's All About Birds site, a fantastic resource for digging deeper into bird biology.

The Master of Disguise: The Male in Eclipse Plumage

Here's a curveball that trips up even seasoned birders. After the breeding season, adult male Mallards undergo a complete molt called the "eclipse molt." They lose all their bright feathers at once and grow a temporary set of drab, brown, female-like feathers. This is for camouflage while they're also flightless during the wing molt.

During this period, which lasts a few months in late summer, drakes look remarkably like females. But they often retain some clues. The most reliable one? The bill color. Male Mallards in eclipse plumage typically keep their solid yellow or olive-yellow bills. Females have orange bills mottled with black. Also, look for a vestige of chestnut on the chest or a slightly more reddish-brown breast compared to the grayer-brown of a true female. The head might also have a faint greenish wash if you catch the light right, but it won't be the solid emerald cape.

So, a duck that looks like a female but has a bright yellow bill is almost certainly a male in his summer disguise.

Mallard Look-Alikes: The Hybrid Factor

Mallards are the Casanovas of the duck world. They readily hybridize with other closely related species, and these hybrids can create bewildering combinations of features. A common hybrid is the Mallard x American Black Duck or Mallard x domesticated duck (think of the odd ducks at your local park).

A hybrid might inherit the body shape and color of a female Mallard but patches of iridescent green from its mallard parent. This creates a duck that defies simple categories. Before you conclude you've found a female Mallard with a green head, it's worth considering if it might be a mixed-heritage bird. Identification gets really fuzzy here, and sometimes, you just have to shrug and label it "weird mallard hybrid." It's not a satisfying answer, but it's an honest one.

How to Actually Tell Male and Female Mallards Apart (It's Not Just the Head)

Relying solely on head color is a rookie mistake that will lead you astray, especially with young birds, eclipse birds, and hybrids. You need a whole-body ID checklist. Think of it like recognizing a friend from a distance – you don't just look at their hair color.

| Feature | Typical Adult Male (Drake) in Breeding Plumage | Typical Adult Female (Hen) |

|---|---|---|

| Head | Iridescent green with narrow white neck ring. | Mottled brown and buff, with a dark eye line. |

| Bill | Solid yellow to olive-yellow. | Orange to brownish, splotched with black. |

| Breast | Rich chestnut brown. | Paler, streaked brown and buff. |

| Body | Gray back and sides, black rear. | Overall mottled brown, tan, and black. |

| Tail | Has distinctive curled black upper tail feathers ("sex feathers"). | Straight, pointed tail feathers. |

| Voice | Soft, raspy call or whistle. Not the classic "quack." | The loud, classic descending "QUACK-quack-quack." |

| Behavior | More prominent, often seen "head-pumping" or chasing. | Often more subdued, especially when nesting. |

See? The bill is a dead giveaway most of the time. The tail curls are a slam dunk for a mature male. The voice is a huge clue. You have to put all these pieces together. If the head is green but the bill is orange-and-black, something's up. If the body is brown but the tail has curls, it's a male in eclipse.

The green head is the star of the show, but the supporting actors (bill, tail, voice) often tell the real story.

Common Questions Birders Ask (The FAQ We All Need)

Final Thoughts: Embracing the Uncertainty

The question "Can female Mallards have green heads?" is a fantastic gateway into deeper bird understanding. It forces you to move past the pretty pictures and grapple with the messy, complicated reality of animal biology. The answer challenges the simple dichotomies we love.

Most of the time, the green-headed duck is a male. Sometimes, it's a male in disguise. Very, very rarely, it might be a female whose body is telling a different story. The fun isn't just in getting the answer right, but in learning how to ask better questions: What's the bill like? What season is it? How is it behaving?

Next time you're at the pond and see a duck that makes you pause, enjoy the mystery. Take a mental checklist. Note the details. That moment of confusion is where real learning happens. You're not just identifying a bird; you're reading a story written in feathers, a story about age, health, season, and sometimes, genetic chance.

So, keep looking. That odd duck might just teach you more than a dozen textbook-perfect ones. And you'll have a great story to tell about the time you really had to ask, can female Mallards have green heads?

Reader Comments