Quick Birding Guide

- Why Size and Shape Beat Color Every Time

- Building Your Mental Framework: The Size Categories

- The Shape Library: From Beaks to Tails

- The Power of the Silhouette: Recognizing Groups at a Glance

- Practical Application: Common Confusions Solved

- Behavior: The Dynamic Part of Shape

- Putting It Into Practice: Your Field Exercise

- Tools and Resources to Help You See

- Answering Your Bird ID Questions

- Final Thoughts: Embrace the Process

Let's be honest. Most bird guides, and a lot of beginners, get it backwards. They jump straight to the flashy stuff—the red breast, the blue wing patch, the yellow stripe. And look, color is great. But it's also the most unreliable trick in the book. Light changes. Seasons change. Birds molt. A bright red male Cardinal in summer looks totally different from a duller female, and a juvenile... well, good luck.

I spent my first year of birding utterly confused because of this. I'd see a brownish bird and flip frantically through my guide, trying to match the exact shade. It was a nightmare. Then an old-timer at a wildlife refuge saw me struggling and said something that changed everything: "Stop looking at the paint job. Look at the car."

He was talking about bird identification by size and shape. The silhouette. The proportions. The way it holds itself. This is the skeleton key to birding. It works in bright sun, at dusk, in fog, against a backlit sky. It works for males, females, and kids. Once you learn it, you start recognizing birds from a distance, long before you can see any color detail. This guide is about building that skill from the ground up.

Why Size and Shape Beat Color Every Time

Think about recognizing a friend from far away. You don't identify them by the color of their shirt—that changes daily. You recognize their height, their build, the way they walk, the shape of their silhouette. It's the same with birds. Mastering bird identification by size and shape gives you a robust, all-weather skill.

Lighting plays cruel tricks. A bird in deep shadow can look black. A bird in harsh midday sun can look washed out. But its shape? A hawk's hooked beak and broad wings are unmistakable whether it's backlit or not. Season is another color-killer. Many brilliant warblers in spring transform into dull, confusing "confusing fall warblers" later in the year. Their shape, however, stays exactly the same—a tiny, sharp-beaked, active body flitting through leaves.

My biggest "aha" moment was with the common Black-capped Chickadee and the White-breasted Nuthatch. At a glance in a tree, they're both small, black, white, and gray birds. But the chickadee is a plump little ball with a round head and no neck. The nuthatch is sleek, pointy, and has this incredible habit of walking head-first down tree trunks. The behavior is a clue, but it stems from its body shape and strong feet. You learn one, you never mistake it for the other, even in silhouette.

Building Your Mental Framework: The Size Categories

Before we get to specific shapes, we need a common language for size. Forget exact inches. Think in common, everyday comparisons. This is how birders talk in the field.

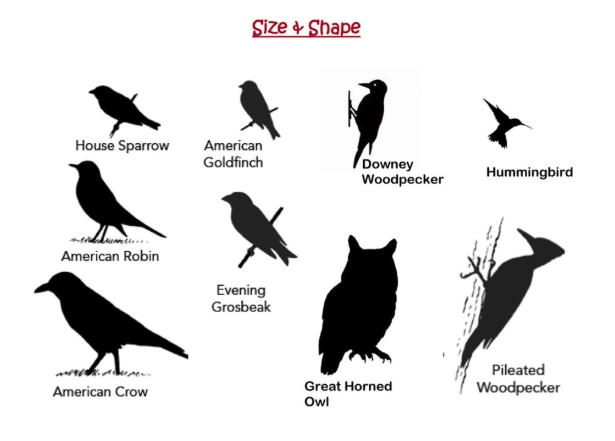

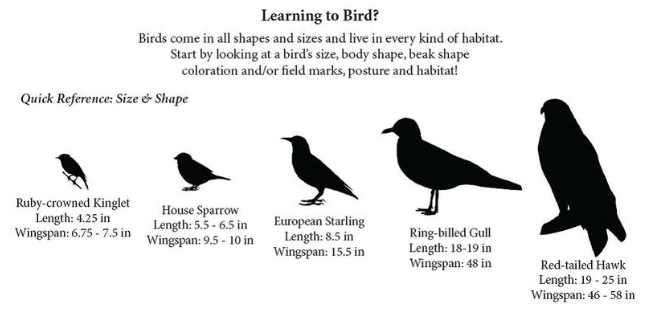

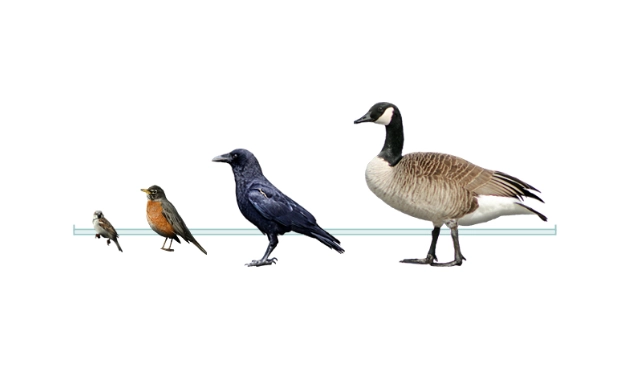

Here’s the hierarchy, from small to large. Memorize these like you know your alphabet:

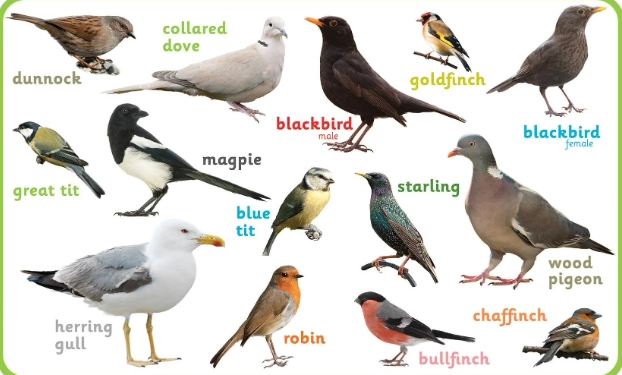

- Sparrow-sized or Smaller: This is your baseline. Think House Sparrow. This group includes warblers, kinglets, wrens, and most finches. They're tiny, often seeming hyperactive.

- Robin-sized: The American Robin is the classic benchmark. This includes birds like mockingbirds, starlings, and jays (though jays can be bulkier). It's a significant step up from sparrow-size.

- Crow-sized: Another perfect benchmark. American Crow. This covers many hawks, ravens (which are actually larger, a key point!), and smaller herons.

- Goose-sized or Larger: Canada Goose is the go-to. This is the realm of large herons, eagles, swans, and vultures.

See how that works? You see an unfamiliar bird and your first question is: "Is it sparrow-sized, robin-sized, or crow-sized?" That instantly eliminates 75% of the possibilities in your field guide. It's the first and most critical filter in bird identification by size and shape.

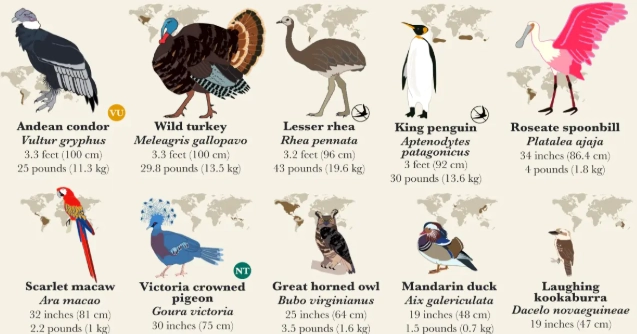

The Shape Library: From Beaks to Tails

Now for the fun part—the shapes. This is where you learn to read the silhouette. Let's break down a bird into key components.

Beak (Bill) Shape: It's All About the Job

The beak isn't just for eating; it's a billboard advertising the bird's lifestyle. This is a huge part of the "shape" puzzle.

A short, conical, seed-cracking beak screams "finch" or "sparrow." A long, slender, forceps-like beak belongs to a warbler or gnatcatcher, perfect for picking insects from leaves. The dramatic, dagger-like beak of a heron is built for spearing fish. A hawk's sharply hooked beak is for tearing meat. Ducks have broad, flat bills for straining goodies from water.

I remember confusing a Northern Flicker (a woodpecker) with a robin from a distance once. Both are robin-sized and have spotted underparts. But the flicker was on the ground, and when it turned its head—bam—that long, pointed, slightly curved beak for probing ants was a dead giveaway. The robin has a straight, general-purpose beak. The beak told the whole story.

Body and Silhouette: The Overall Vibe

This is the gestalt, the overall impression. Some birds are plump and round like a feathered tennis ball (chickadees, many sparrows). Others are sleek and elongated like a torpedo (cormorants, loons). Some are incredibly upright and slender (many herons), while others are horizontal and low-slung (waterfowl like ducks).

Pay attention to the neck. Ducks and geese have relatively short necks (except when stretching). Herons and egrets have long, S-curved necks they keep folded in flight. Swans have very long, straight necks. The presence or absence of a visible neck is a major clue.

Tail Shape and Length

Don't ignore the back end! A Mourning Dove has a long, pointed tail. A Northern Cardinal has a long, rich tail, but it's more squared-off. A wren's tail is often cocked straight up. Woodpeckers like the Northern Flicker have stiff tail feathers they use as a prop against trees. Barn Swallows have incredibly long, forked "streamers." The humble House Sparrow has a short, square tail. It's a defining feature.

Legs and Feet

Often overlooked, but telling. Long, stilt-like legs place a bird in the shorebird or wader family (herons, sandpipers). Very short legs that seem barely there are common on swallows and swifts, birds built for almost constant flight. Webbed feet mean a swimmer (ducks, geese, gulls). Powerful, taloned feet mean a predator (hawks, owls).

Putting It All Together: A Shape Cheat Sheet

When you see a new bird, run through this mental checklist: 1) Size (sparrow/robin/crow/goose?), 2) Beak shape (short/conical, long/pointed, hooked, flat?), 3) Body silhouette (plump, sleek, upright?), 4) Tail (long/short, forked/rounded?), 5) Legs (long/short, color?). Answering just the first three will get you amazingly close.

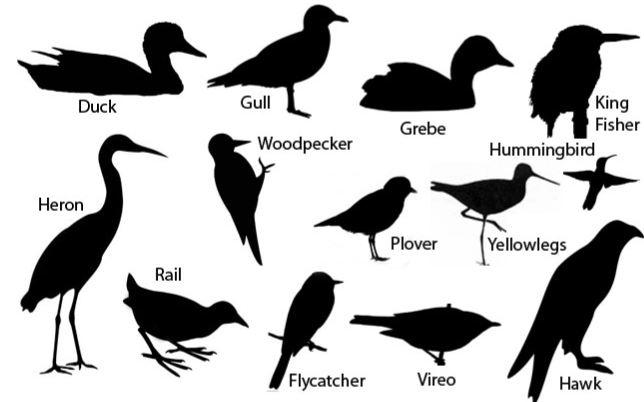

The Power of the Silhouette: Recognizing Groups at a Glance

This is where bird identification by size and shape pays its highest dividends. You can start placing birds into broad, recognizable families instantly, just from their outline, especially in flight or at a distance.

Let's look at some classic silhouettes.

The "Flying Cross" (Accipiters like Sharp-shinned & Cooper's Hawks): These bird-hunting hawks have a classic shape: broad, rounded wings and a very long, rudder-like tail. They're built for maneuvering through forests. Seeing that long tail is often your first clue it's not a Red-tailed Hawk.

The "Flying Door" (Buteos like Red-tailed Hawks): These are the soaring hawks you see over highways. Large, broad bodies with long, broad wings and a shorter, fanned tail. They look sturdy and powerful, built for riding thermals.

The "Flying Tumbler" (Swallows and Swifts): Sickle-shaped wings and a short, forked or squared tail. They look like they're made of pure air, zipping and turning erratically over fields and water. Their tiny feet are practically invisible.

The "Flying Anchor" (Cormorants): A long neck, a heavy, low-slung body, and a relatively long tail. They often fly in a straight line with neck kinked, and their flight seems labored compared to a goose. It's a distinctive, almost prehistoric look.

The "Little Ball" (Most Small Perching Birds/Passerines): This is the default shape for sparrows, finches, warblers at rest. A compact, rounded body with a clear head and a tail of varying length. The differences are in the finer details of beak and tail.

Training your eye for these silhouettes is a game. I sometimes sit on my porch at dusk and try to name birds just by their black shapes against the fading sky. It's hard, but it's the best practice there is.

Practical Application: Common Confusions Solved

Let's apply this to real-world problems. These are the pairs or groups that trip up almost everyone at first.

Crow vs. Raven

This is the classic. Both are big, black, and smart. Color is useless. Size is your first clue—ravens are significantly larger, about the size of a Red-tailed Hawk. But at a distance, scale is hard. So look at the shape. Crows have a fan-shaped tail. Ravens have a distinctive wedge-shaped or diamond-shaped tail, especially noticeable in flight. The raven's beak is heavier and shaggier feathers at the throat give it a "bearded" look. In flight, a crow's wingtips look more fingered, while a raven's are more splayed. The raven's call is a deep, croaking "crroak" versus the crow's familiar "caw." It's a suite of shape and size clues.

Downy vs. Hairy Woodpecker

A nightmare for beginners. Their plumage patterns are almost identical—black and white with a white back. The Hairy is larger, but again, scale is tough. The foolproof size and shape clue? Look at the beak in relation to the head. The Downy's beak is short and stubby, shorter than the length of its head from front to back. It looks dainty. The Hairy's beak is a long, sturdy chisel, as long as or longer than its head. It looks like a serious tool. Once you see this, you'll never mix them up again.

Sharp-shinned Hawk vs. Cooper's Hawk

Even experts debate these. Both are accipiters (the "flying cross" shape). The Cooper's is larger (crow-sized vs. jay-sized), but females are larger than males, so overlap happens. Forget size. Look at the shape of the head and tail. A Sharp-shinned Hawk's head looks small, barely projecting beyond the leading edge of its wings in flight. Its tail is square or notched. A Cooper's Hawk has a larger head that projects noticeably. Its tail is rounded, often with a broad white tip. The Cooper's also has a more "necky" appearance. It's subtle, but it's all about those proportions.

Behavior: The Dynamic Part of Shape

Behavior is motion, and motion reveals shape and purpose. How a bird moves is a direct extension of its build.

Does it cling vertically to a tree trunk? That's a woodpecker, nuthatch, or creeper, all with stiff tails and strong feet for support. Does it walk on the ground with a purposeful strut? Think robin, starling, or blackbird. Does it bob its tail or body constantly? That's a classic move for Spotted Sandpipers (full-body bobs) and many wrens (tail flicks). Does it soar in wide circles without flapping? Likely a hawk, vulture, or eagle. Does it hover in one spot like a hummingbird? Well, that's a hummingbird—a shape and behavior combo that can't be mistaken for anything else.

Flight style is perhaps the most diagnostic behavior. The deep, slow wingbeats of a heron vs. the rapid, stiff wingbeats of a duck. The bounding, flap-flap-glide rhythm of a woodpecker. The erratic, bat-like fluttering of a goldfinch. Start paying attention to the rhythm as much as the shape itself.

Putting It Into Practice: Your Field Exercise

Reading is one thing. Doing is another. Here’s a simple plan to train your bird identification by size and shape muscles.

Week 1: The Usual Suspects. Pick three common birds in your yard or local park. Let's say a House Sparrow, an American Robin, and an American Crow. Don't just look at them. Study them. Sketch their outline (no artistic skill needed). Note the sparrow's plump body and short, thick beak. Note the robin's fuller breast and upright posture. Note the crow's all-business profile and stout beak. Watch how they move. Burn their basic size and shape into your brain until you know them in your sleep.

Week 2: The Silhouette Challenge. Go out at dawn or dusk, when birds are often backlit. Try to identify them only by their black shape. Use your three known birds as scales. Is that new shape bigger than a robin but smaller than a crow? What's its beak like? Is its tail long or short? It's frustrating at first, but incredibly effective.

Week 3: Focus on a Feature. Spend a whole week just looking at bird beaks. Ignore colors. Just categorize every beak you see: conical (finches), thin & pointed (warblers), hooked (hawks), long & spear-like (herons). You'll start seeing patterns everywhere.

There's no shortcut. It's like learning the chords on a guitar. At first, it's awkward. Then it becomes muscle memory.

Tools and Resources to Help You See

You don't have to do this alone. Use tools that emphasize shape.

A good field guide is essential, but use it smartly. Don't just flip to the color plates. Study the silhouette diagrams that many modern guides include. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology's "All About Birds" online guide is a phenomenal free resource. Look up a bird you know, like the Red-tailed Hawk. They have tabs for "ID Info" that break down size, shape, color pattern, behavior, and even similar species comparisons. It's a masterclass in identification. I use it constantly to check my work.

The National Audubon Society's online guide is another fantastic, authoritative source with great photos that often show birds in different postures and lighting.

Consider a guide focused specifically on shape. Books like "The Crossley ID Guide" series use realistic, composite images that place birds in their typical habitats and show them at different distances and angles. It forces you to work on size, shape, and impression rather than just matching a perfect portrait.

And honestly, one of the best tools is a pair of binoculars that you can bring into focus quickly. Practice on stationary objects. Get used to finding a bird and adjusting the focus until the shape is crisp. A blurry bird teaches you nothing.

Answering Your Bird ID Questions

Final Thoughts: Embrace the Process

Learning bird identification by size and shape isn't a destination; it's a shift in how you see the world. It makes you a more observant, more patient person. You start noticing details you never did before.

You'll make mistakes. I still do. Last week I called a distant Cooper's Hawk a Sharp-shinned for a full minute before the shape of its head finally clicked. It's humbling. But that moment of realization, when the pieces of size, silhouette, and behavior snap together and a name pops into your head—that feeling is pure magic. It turns a blur of feathers into an individual with a story.

Put down the color-focused app for a bit. Grab your binoculars, find a comfortable spot, and just watch. Start with the big picture—the size, the shape, the way it moves. The colors will still be there, but now they'll be the finishing touch, not the whole puzzle. Happy birding.

Reader Comments